He found his way home.

In my interior, and totally subjective map of Ireland, Waterford was always a bit of an eerie black spot.

Certainly, in my family, over in Limerick and Clare, we stayed well away from Waterford. Deep in the recesses of my childhood memory, I can hear my Nanna mumbling something to the effect of “don’t go to Waterford or you’ll get TB”. I never did get a proper explanation of that. Either Waterford or the TB. It was just this lingering no-go area on my own unconscious map of Ireland. This was the ripple effect, lapping around my tiny ankles through the mists of time.

Ireland. No-one is far from dark secrets here. Just start digging, and see for yourself.

In October 2014 I got a welcome phone-call from my Dad’s Kilkenny first cousin, inviting me out to Sandycove to meet newfound relatives. Pat had been digging around in the Mulrooney family tree. While doing so, he encountered an extraordinary man from Australia who was on the exact same quest from down under – except this man was being funded by the Australian and the British government. Both their searches led them to Waterford – where lo and behold they found each other – relatives.

So off I went to welcome this mysterious long-lost relative, whose grandmother apparently was a cousin of my own great-grandfather the “gardener” (as per 1911 census), coachman and estate manager at Belmore/ Jerpointchurch House near Mount Juliet. This out-lying ancestor, cousin of my great-grandfather’s became a midwife in Waterford, where she had moved to from Kilkenny, to marry the postmaster.

“Flesh & Blood”, meeting our heroic relative John Michael Hennessey (2nd from right) at the Hutchinson’s, on October 13th, 2014.

And here was her grandson, septuagenarian John Michael Hennessey, a lovely, quiet-spoken, Australian man, who resembled my own father more than a little. Actual hug! My Dad (b.1941), had always wanted to go to Australia. Little did he realise he had a blood relative in Western Australia, an ill-fated second cousin just a few years older than himself, who had been shipped there at the age of 10 in 1947 as a child migrant.

This quiet elderly man, sitting before me with a warm grin on his face, espousing his heartfelt delight to meet what he termed, his own, dearly cherished “flesh and blood” entered a cruel world in Chelsea, London, in 1936 (or was it Cheltenham? I’m not exactly sure). His mother, May Mary, (also a midwife), had been banished to England by her mother for being pregnant outside of wedlock.

It took a mountain of toil and tears before John, by now 63, would finally meet his much longed-for mother again in 1999. May Mary had been told her baby died. Or was it that he had been adopted into a good English family? I’m not sure. John was told he was an orphan, and fed false information about his origins, including that he was born in Belfast. It was legendary Nottingham social worker Margaret Humphreys, (who was played by Emily Watson in Jim Loach’s 2010 movie “Oranges and Sunshine”), who performed this miracle of reconnection, giving John’s mother 6 years of a brief but ‘beautiful’ relationship with her only child before her death in her 90s.

The road home back to Ireland was a long and arduous one for John, to arrive into this cosy and familial Irish living room where he was being warmly embraced by newfound family in his late 70s. He didn’t go into any detail about the horrific abuse he had been subjected to in his lifetime. No recriminations. Just that smile. A sigh, and a shake of the head. Unspeakable. And a strange sense of relief to be finally, finally home among his own “flesh and blood” – a term of deep significance to him.

Later, I shuddered when I read the gruesome details in John’s painstaking testimony in the April 2014 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Sexual Abuse which was published online, disseminated in copious news reports, and formed part of the 2015/2016 exhibition at the V & A Museum of Childhood, Bethnal Green entitled “On their Own: Britain’s Child Migrants”. The overwhelming thought of our own flesh and blood there. A true hero, our relative John only put himself through the ordeal of recounting the sordid details in order to spare anyone else ever having to live through a similar experience.

With the tantalising promise of sunshine, kangaroos, and oranges, at the age of 10 John was one in a boat full of little children shipped from “Nazareth House”, Bristol, to Fremantle, Western Australia, where they landed in November 1947 to great fanfare, and a welcoming committee headed by the Archbishop of Perth himself. They believed they were on a great adventure. But where were the promised oranges? The kangaroos?

“Being young and excited, and this is where trust comes in, a word which must go through this whole thing, trust, we trusted everything the nuns told us. We trusted everything the Brothers told us. The Brothers in particular told us about kangaroos. Kangaroos would take us to school, there was fruit everywhere and we were young excitable boys and we had no prejudice in those days. We were just young innocent children”. (John’s June 1998 testimony in the House of Commons)

The only sunshine was that of the relentless sun they had to labour under to build their own orphanage at the forsaken “Boys’ Town”, Bindoon, where they would be sadistically beaten and abused by “carers”, the worst of whom, sorry to say, were Irish. As a result of what John was forced to endure here, he could never trust anyone enough to enjoy an intimate relationship throughout his entire lifetime. His sadness about not having his own children was palpable.

A painter and decorator without any birth certificate, from somewhere deep within him, in 1999 John overcame this crushing abuse and injustice to organise a meeting with Tony Blair and elicit a personal apology from him on behalf of all his fellow victims. He became Deputy Mayor of Campbelltown, outside Perth:

“I just cannot understand how I got through, with drivers’ licences…I still do not know. The classic has to be that I was Deputy Mayor of the city of Campbelltown. It is a city of 150,000 and half the population is under 21. The people for some unknown reason took to me and I went straight on. I was on that council. Nobody questioned it, but it was illegal because you were supposed to be an Australian citizen. I did not even have that birth certificate. I was not even an Australian citizen and yet I sat on that council for four years as Deputy Mayor. That is the type of thing. I must say the staff there for some unknown reason took to me, but I never told them my story. They said to me, after I left the council, when this came out, John, why did you not tell us the story? I said I wanted them to accept me as I am. I did not want any sympathy.” (John’s testimony to House of Commons).

He even negotiated compensation for his fellow victims from Gordon Brown. Beyond this tireless work with Margaret Humphreys of Child Migrants Trust, getting justice for himself and his fellow survivors, he was also awarded an Order of Australia Medal (OAM) in 1999.

I feel a strange mixture of ancestral shame (at how John and his mother were treated by my family), and pride (at John’s extraordinary achievements), when I think of John, who took his final breath in this cruel, unfair world in May 2016 (just before that exhibition “On Their Own: Britain’s Child Migrants” came to a close in the V & A Museum of Childhood). My flesh and blood. All of our flesh and blood. And the unimaginable effort he made to connect with us, for us to hear his story and finally embrace him. All of this we may never have known.

Which brings me back to my granny’s 1970 mumblings, about which I had to wait until 2014 for my my newfound relatives to enlighten me.

In a strange twist of fate, after the pregnant, alone, May Mary was banished from Waterford in the 1930s, her mother – who had banished her – became a carrier of TB, and tragically lost all of her remaining children to the disease. A whole Waterford family – except the “unlucky” unmarried pregnant one who was banished – wiped out by TB. Could this possibly have been the universe’s response to her banishment of John’s pregnant mother? Karma? Perish the thought. Little did my Nanna (blurter of “don’t go to Waterford or you’ll get TB”), know the deeper, hidden layers, of that family’s tragic tale of Greek proportions, and the heroic acts to come on behalf of one John Hennessey.

John Hutchinson, the elderly man whose cosy south Dublin house we were invited to, believed he had no relatives, until he met John Michael Hennessey – his first cousin. John’s Hutchinson’s mother – sister of the banished May Mary – had died of TB when he was a very small child, and he was subsequently raised in a most unpleasant orphanage-style institution in Ireland as his widowed father couldn’t cope with raising a small boy on his own. He just shook his head when asked about it too.

The joy of this pair of elderly cousins divided by continents and secrets finally finding each other was poignant. How lucky we are that John made the Herculean effort to follow his homing instinct, and came back to reconnect with us, in the place he was made – even though we may not deserve him and his exceptional acts of valour. Like a wounded migratory bird, he found his way home.

So let’s honour John’s memory, and his wishes, by reminding ourselves of the shameful, atrocious injustices he was put through, what he was robbed of, and pledging never ever to acquiesce unquestioningly to authorities that allow such abuses and such complicit secrets to creep into our society ever again. We have to think for ourselves. Question. Take responsibility. And stand up when the archives of the Mother and Baby homes are being sealed for 30 years. What? Irish government 2020 you cannot be serious. Put your hand up and object.

Survivors you are seen and heard.

It’s time to own this. Our family – all the strength and all the cruelty. The good and the bad. Ireland. My flesh and blood. Our flesh and blood, all of ours there.

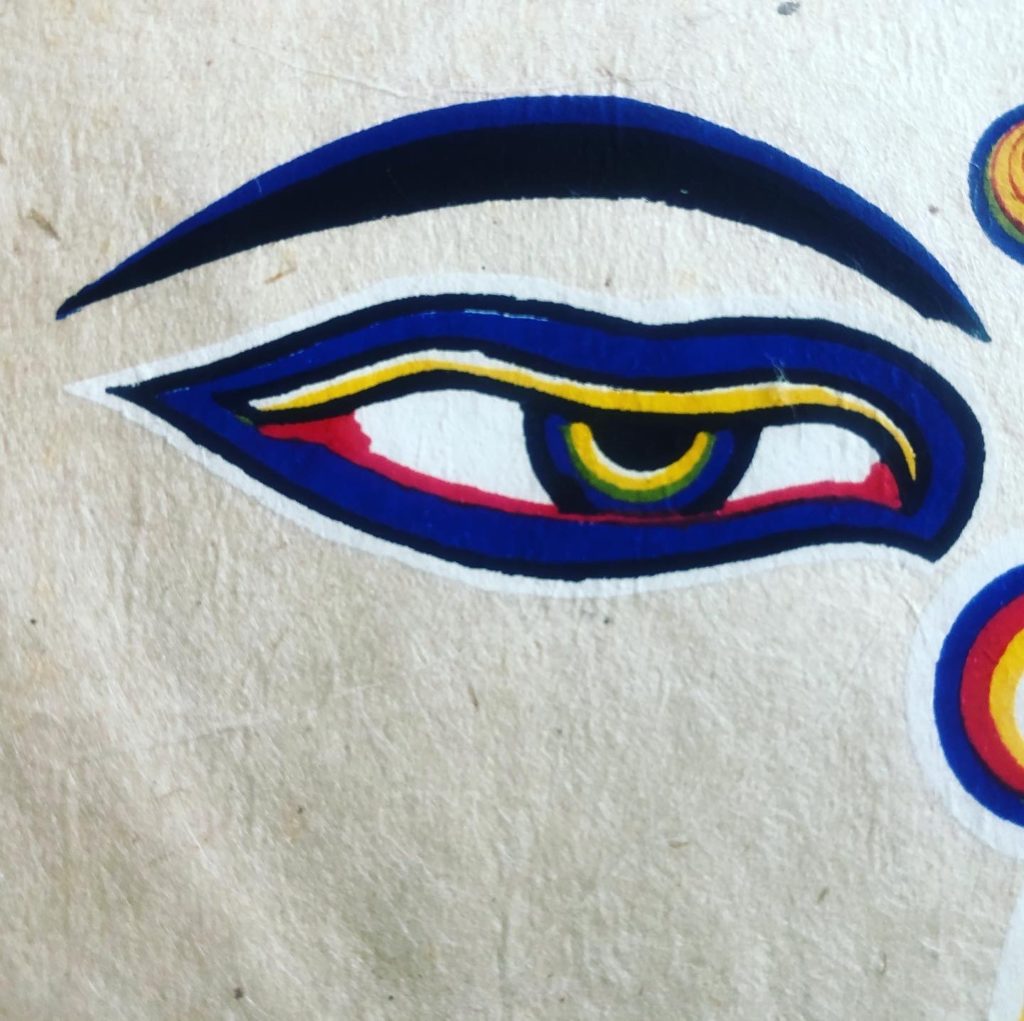

Survivors you are seen and heard. The world is watching. Join us, draw an eye on your hand to show your solidarity and share on social media. This outrageous sealing of the Mother and Babies Homes Archive legislation is complex, and challenging to get one’s head around. BUT “the President’s decision to sign this legislation leaves it open to any citizen to challenge the provisions of the Bill in the future.” In other words, our president is throwing serious doubt on the bill while signing the bill into law. Not signing would have created a cul de sac where nothing could be challenged. And, obviously this new legislation must be challenged. Because, the truth will set you free. And nobody deserves the truth more than survivors of Mother and Babies homes.

This outrageous sealing of the Mother and Babies Homes Archive legislation is complex, and challenging to get one’s head around. BUT “the President’s decision to sign this legislation leaves it open to any citizen to challenge the provisions of the Bill in the future.” In other words, our president is throwing serious doubt on the bill while signing the bill into law. Not signing would have created a cul de sac where nothing could be challenged. And, obviously this new legislation must be challenged. Because, the truth will set you free. And nobody deserves the truth more than survivors of Mother and Babies homes.

Then there is that ripple effect out to the whole society at large. The more you try to bury it, the greater those ripples lapping around more ankles and rising, rising. Leading inexorably to more untold and unimaginable tragedy of Greek proportions for all of us. So, if nothing else will convince you, powers that be, for your own sake, unseal the archives.